|

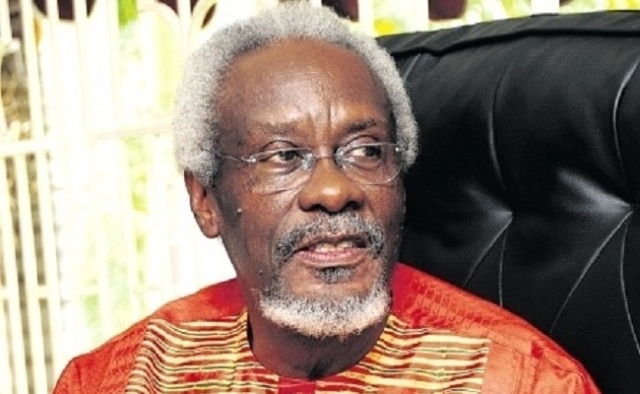

| THE MOST HON. P. J. PATTERSON, ON, OCC, PC, QC |

Inaugural PNP YO Lecture at Excelsior High School - Thursday 18 July 2013

INTRODUCTION

This

Lecture forms part of a series, during the 75th Anniversary of the

People’s National Party, intended to reflect upon our historical legacy and

advance our discourse on a range of contemporary issues devoted to our social,

economic and cultural evolution as a country and as a people.

I

must commend the PNP Youth Organisation for hosting this lecture and, once

again, being first off the mark. The

occasion is itself of great significance as you mark your 45th

Anniversary for it was here at the Excelsior High School Auditorium that the

PNP YO emerged on the political stage.

Yours

is now a mature Organisation, which has fostered the engagement of the PNP with

a broad coalition of youth support that

has yielded benefits to the mutual advantage of both the Party and its

Affiliate over the preceding years.

How

fitting it is that the event coincides with the 95th Birthday of

Nelson Mandela, an icon in the struggle for freedom, for justice against the

cruel indignity of apartheid!

The two political institutions which played a seminal role in

the shaping of the Jamaican society are currently celebrating milestone

achievements. The Jamaica Labour Party

deserves our warm and sincere congratulations on its 70th

Anniversary. For seven decades, the

Jamaica Labour Party and the People’s National Party have managed to keep our

democracy alive.

I have said before and, once again assert, that if we

objectively assess the performance of both political parties over these years,

there are successes for which we can each take credit and failures which we should

admit.

While we will always have our differences as part of the cut

and thrust of the political process, we must always strive to remain true to our history.

I shall not follow someone else’s contrived version of our

past that would make one Party the “saviour” and another the “villain.” That would only serve to falsify the chronicle and perpetuate the divisive nature of our

political process.

Let me begin with “mashing down one lie”.

Scholarly research, for example, has shown that the growth of

the 1960s was sustained by the strong economic foundations laid by the PNP

Administration of Norman Manley between 1955 and 1962. It could not have suddenly happened after

1962. A country’s development is not just

a series of events, but an endless process of activities. It takes away nothing from a truly honest political

figure to recognize and acknowledge that the economic growth between 1955 and

1965 was the highest in any single decade in our country.

As we inaugurate these Annual Lectures, I want the YO to devote its energy to ensuring

that the legacy of our fore parents is forever protected from any attempt to distort their contribution

for the sake of political one-upmanship.

If we allow the distortion of the people’s history to go unchallenged, then

the common cause which bound us in slavery, colonialism and independence and that

must provide the meaning and purpose of our future development would have been

fractured.

THE REAPPRAISAL REPORT

Following

its defeat in 1967, the second in the Independence era, Norman Manley insisted

that there be a critical review of the Party’s organization and administrative

structure to make it more efficient, responsive and attractive.

I

was entrusted with the responsibility to chair a Reappraisal Committee,

comprised of Party stalwarts and known supporters with diverse areas of

political experience and professional competence.

Our

instructions were to avoid any compromise on the core values and tenets of the

Party in an expedient route to political office. Cardinal principles had to be maintained

while pursuing sound political strategies to secure State power – the two

should not be seen as mutually exclusive.

Several

structural changes were proposed and subsequently approved by a special Party

Conference in 1968 –

* The

Report recommended the creation of a Party Secretariat with a competent staff

to support the General Secretary. These

were a Public Relations Officer,

(Patrick Cooper); a Fund-raising Officer

(Robert Pickersgill); a Research

Officer, (Kenneth Chin-Onn); a Youth

Organizer (Leroy Cooke).

* A new

post of National Organiser, (Courtney Fletcher) was created to take charge of

operations in the field.

* Other

key features of the Report included a recommendation to separate the role of

the Party President from that of Party Chairman. Arising from that recommendation David Coore became the Party’s first

Chairman.

* There

was also a recommendation to elect four Vice Presidents of equal status, and so

discontinue the practice of electing a first, second, third and fourth Vice

President. The four candidates

receiving the most votes would be elected to fill the four posts.

Another

key recommendation was to decentralize the Party by establishing six political regions and vesting in them clear areas of

constitutional responsibility and oversight.

That

recommendation was not implemented until 1974.

THE BIRTH OF THE YO

A

year before the Report of the Reappraisal Committee, Norman Manley had expressed

the Party’s concerns about the involvement of young people in the development

of the new Jamaica. He said: “youth power in the modern world is not a

joke. It is a tremendous reality, which

has made new leaders and brought down old governments. Youth power is the repository of so much

faith and hope and new energy and unexpected dedication, that any wise observer

will falter at the thought that any generation coming into being should not be

making search for its own mission, and informed with a desire to achieve it.”

Among

our recommendations was the need to attract and connect with the youth of the

population and to do so through the establishment of a Youth Organisation as an Arm of the Party.

Elected

as a Party Officer in 1969, I understood the importance of this task and was the

Vice-President assigned to devote the time and energy in building a strong and

vibrant youth movement within the People’s National Party.

WHERE

DO WE BEGIN?

The

activism of young Jamaicans in the political process certainly preceded the

formation of the People’s National Party (PNP) in 1938.

When

Solomon Alexander “Sandy” Cox launched

The National Club in 1910, Jamaica’s first nationalist organization, the two

secretaries were 23-year-old Marcus Garvey and 21-year-old Wilfred Domingo.

Domingo

became a founding member of both the Jamaica Progressive League and the

People’s National Party.

In

1934, thirty-year-old Osmond Theodore

Fairclough returned to Jamaica from Haiti, where he had held managerial

positions in the National Bank. When he

presented his credentials to the managers of two Canadian commercial banks

operating in Jamaica, one offered him the job of a porter. Fairclough immediately took the decision to

invest his time, energy and resources in the formation of a political Party

that would radically change Jamaica’s political and social fortunes.

In

1937, Fairclough recruited 25-year-old Frank Hill to launch a weekly newspaper, The Public Opinion, which quickly became the

organ of the national movement.

Kenneth George Hill

was 27 years old when he founded the National Reform Association (NRA). Earlier in 1938, he was at the centre of the labour rebellion

and later led the dissolution of the NRA to make way for the PNP.

Howard Cooke was

a 21-year-old teacher at Mico Practising School when O.T. Fairclough requested

that the Principal, J. J. Mills, recommend two young members of the Jamaica

Union of Teachers (JUT) to represent that body at a conference to discuss the

formation of the PNP. He became the

youngest member of the steering committee which wrote the Party’s Constitution.

OUR NATIONAL HEROES

We

could go even further back in history.

When

the Maroon Treaty was finally signed in 1739 – Nanny had become a skilled and persistent leader for some twenty

years before the Treaty was agreed.

That places her in her late twenties when she started her protest

against the greatest military power at that time.

It

is believed that Samuel Sharpe was

born in 1801. What is, however, certain

is that he was hanged on May 23, 1832.

That would have meant that he began his advocacy for Abolition in his

twenties, if not before, as he was only

31 years old at the time of his execution.

Of

more recent vintage were Paul Bogle and

George William Gordon. Bogle was

born around 1820. He was executed in

1865 – he would therefore have been in his mid forties at the time of his

execution. For him to have achieved the

position of a leader among his contemporaries, sufficient to have mobilized and

led them in Rebellion – he must have started his brand of advocacy in his early

adulthood.

Both

he and William Gordon were in the same age cohort. Obviously, William Gordon also began his entry into prominence while he

was quite young.

TRACING OUR PAST

“The

Youth are the Trustees of posterity” – Disraeli

The

past is fixed, we can no longer change its course nor influence its outcome,

but it demands our full understanding and our own narrative.

Too frequently we hear the younger generation claiming they

have no interest in the past. They only

want to hear how we are going to deal with the present. Our founding fathers and mothers hold little

importance for them and so our past becomes vaguely perceived.

Our own National Hero, the Right Excellent Marcus Garvey –

recognised “that history is the guidepost of our destiny” and without that

sense of history we can gain no respect or occupy any pride of place on the

world stage.

Like

a nation, the Party’s history is also the living embodiment of its being. The principles and traditions that are

embedded in the history of the PNP remain the very soul and life of its

existence today.

Any

understanding of the PNP YO in the context of its role within the Party over

the past decades must therefore begin with a descriptive analysis of the Party,

its origins, principles and objectives in the context of the times and

circumstances which foreshadowed its formative years.

TRACING OUR POLITICAL ROOTS

When

the economic consequences of the Great Depression began to take its toll in

Europe during the 1930s, the strategy of the British Colonial authority was one

of ‘self-insulation’ by transferring the burden of economic recovery to its

colonial subjects.

There

was an immediate backlash.

Throughout

the British West Indies, the people reacted in waves of demonstrations, strikes

and civil protests. The policies under

Crown Colony rule had provided the seeds of social discontent through a clearly

defined class/colour hierarchical structure, and deprived the descendants of

slaves from having any voice, or say in the determination of the government to

rule on their behalf.

After

the Morant Bay rebellion, the Colonial

powers had resorted to an autocratic Crown Colony regime – a covertly

repressive system, which Norman Manley described as “a perfect instrument for

the degradation of political life, for it gave the illusion of power without

the reality of responsibility.”

The

social and economic servitude of the Jamaican masses was to provide the

catalyst for the unrests that gripped the entire Caribbean. There was no social

cohesiveness or sense of community. The

Moyne Commission, established to investigate the social and economic conditions

which led to discontent across the West Indies, noted the social malaise which

engulfed the islands and “a declining sugar industry supporting an estate

labour force by means of an exploitative task work system [and] with wages so

low that in many cases... it barely exceeded the rate introduced after

Emancipation.”

RESISTANCE

By the middle of the 1930s the Jamaican society was

caught up in the anxieties of social, economic and political change. The need for a political party dedicated to

the cause of the working class became very obvious. Pioneers like H. P. Jacobs, Edith

Dalton-James, N. N. Nethersole, Vernon Arnett, W. G. McFarlane, Rev. O.G. Penso and William Seivright, were

among a group of largely young professionals infected with a restless urge for

change. It was Norman Manley to whom

they turned to provide the intellectual leadership.

At

the launch of the People’s National Party on September 18, 1938, Norman Manley

admitted that the series of uprisings

had forced him to stop and take a check of the political situation. Among the things which struck him forcibly

was that “the democratic institutions of

this country have long since ceased to lead public opinion or to inspire

confidence in any quarter of this island”.

Manley

was adamant that the Party’s name include “People’s because it was intended to

serve the masses of the country.

“It

is perfectly true that the interests of all classes of people are bound

together. But it is equally true that

there is a common mass in this country whose interest must predominate above

and beyond all other classes, because no man is democratic, no man is a sincere

and honest democrat who does not accept the elementary principle that the

object of civilisation is to raise the standard of living and security of the

masses of the people.”

He was just as determined

that it be called “National” because it had to be seen to be about the

development of Jamaica as a whole rather than any single component.

The

Party was conceived as a political vehicle that could embrace all those who

were committed to the building of a nation and sought the long-term well-being

of Jamaicans rather than an easy band-aid.

He

spoke of the growth of progressive ideas in the country, and “most markedly the

growth of opinion among the young men of this country, of the dawn of the

feeling that this island should be their home and their country”.

What

were the underlying principles governing

the Party’s formation?

Firstly, it was to have members abide by the

principles and objectives of the Party.

To it they owed their loyalty rather than to individuals in its

leadership.

Secondly,

the Party had to be democratically structured and built on a spread of Party

Groups.

Thirdly,

the Party had to undertake the task of educating the people of Jamaica “of the

true position they should occupy and what they should expect of their

democratic institutions.”

Fourthly,

the Party needed to be united around its principles and such unity can only be

achieved through discipline and self-sacrifice.

The

formation and growth of the People’s National Party was nurtured in a period of

great intellectual fervour and activism in Jamaica. It was through journalism, with the

publication of progressive ideas in the Public

Opinion; the arts and social agenda with people like Eddie Burke, Leila

Tomlinson, Henry Fowler, Tom Girvan, Philip Sherlock, Roger Mais and Edna

Manley. that broad based support for the Party’s leading role in the pursuit of

the right to self determination would flourish.

W.

Adolphe Roberts, Rev. Ethelred Brown, Rudolph Burke,

C.T

Saunders, Aggie Bernard, A.G.S. Coombs, Willie Henry, helped to spread the

message in our towns, our hills and valleys and abroad.

The

process towards self-determination began with the granting of Universal Adult

Suffrage in 1944, with the People’s National Party championing the cause to end

the grim realities of colonial trusteeship and begin the march towards

constitutional decolonization. The

outcome of our first general elections under Universal Adult Suffrages remains

one of the great ironies of our history.

The

dispiriting effects of colonialism had provided a natural instinct for persons

to look towards messianic leadership, especially when there were no

institutions of support for the people, and where the opportunity for

leadership and government would have been destroyed under crown colony.

FOMENTING THE NATIONAL

SPIRIT

The

PNP saw its role as the fertilizing

agent to develop that national spirit and to build a political consciousness

that imbues the hopes and aspirations of a society based on principles of

equality and social justice.

So

the Party set about to build a movement from the ground up, through strong

grass-roots Party structures, political education and thorough research. The aim was the building of vibrant

community leadership and people empowerment.

Those

early PNP pioneers symbolised the idealism and commitment of an army of young

men and women who understood the importance of laying the foundation for the

building of a movement which could take responsibility for the development and

progress of Jamaica.

From

1945, N. W. Manley had foreseen the need for a youth organisation as an

important requirement to infuse constant

energy and purpose in the Party. During

the 1945 Conference Manley said: “I have preached all the time for a

strong youth movement and I will go on preaching it”.

This

is because the renewal and change necessary for the “the building of the nation

and the shaping of the society, must hold out constant hope for a reinvigorated

youth population, ideally organised and

structured in a youth movement.”

THE BUILDING OF A NEW

JAMAICA

In

the elections of 1949, the PNP won the popular vote but the JLP gained a

majority of seats. Internally, the Party

was badly fractured by combustible tensions.

The

PNP was not about ostracising any class, nor seeking to promote racial

disunity. It never saw the construct of

the Jamaican society on the basis of an ideological ‘class war’. This has to be a central point of our analysis so that it is

not overshadowed by the smoke-screen of

propaganda. We should not fall prey to the popular stream of a

radicalised politics, mooted in

romanticism rather than objective reality.

I am

obliged to stress this point because I believe it is at the heart of our

assessment of the YO’s role in the Party.

We have to ground our analysis in an understanding of the nature, purpose

and objective of the PNP. We have to explain

why it remains the oldest political party in the English-speaking Caribbean, a

testament to the endurance of its philosophy.

After

the painful convulsion in 1952, which resulted in the expulsion of four leading

Members of its left wing, due to perceived differences in ideological

orientation, the Party proceeded to extend its popular outreach and consolidate

its organizational base – to build the movement from the ground up, through

strong grass roots Party structures, political education and research.

With

its first national victory at the polls in 1955, the PNP won a mandate to build

the new Jamaica of which so many of our social pioneers had dreamed.

It

was a response from the people to be rid of a colonial mentality and regime

which had denied a sense of self-worth and a chance to promote self-reliance

through self-government.

The

time had come to build a New Jamaica.

The

focus on planning for economic development became a central theme – the

emphasis was on production, led by agriculture. One slogan was ‘every acre has a use – every

acre needs a man.’

The

question of land reform had both a production and egalitarian emphasis. It was a plank to achieve the economic and

social desirability of the Party’s socialist reconstruction of the Jamaican

society.

For

the very first time, the doors to the best education were opened wide to all

classes of Jamaican children as thousands of free places were offered in

secondary schools on the basis of competitive performance.

PEOPLE POWER

Norman Manley, erudite and sagacious as he was, never

pretended to be the sole repository of all political wisdom. “No man has a prerogative on brains, no one man understands all the

problems of this country. Once you are

decided upon your fundamental principles, power can only be achieved through

unity, and unity can only be achieved by discipline and self-sacrifice.”

Despite several political defeats and disappointments, he

maintained to the very end his belief in the “instinctive wisdom of the

uneducated Jamaican to know what is good and right. Hence his abiding commitment to the

political grass-roots of leadership in

the country” as reflected in the group structure.

As a consequence of this, the PNP never became “leader

centric.” There was no pledge to follow

Norman Manley till we die. Indeed, when

the Party adopted the slogan, “Have faith in Manley, The Man with the Plan”,

those who conveniently coondemned it as heresy,

“because one should only have

faith in God”, failed to see any inherent contradiction with their own

mantra of idiosyncratic leadership.

We must not manipulate a historical account in the interest

of partisan one upmanship by charges that Norman Manley engaged in a Federal Diversion.

Bustamante was entitled to change his mind on the Federal

experiment – but let us not forget that he had previously endorsed W I

Federation without reservation and was pivotal in the founding of the Caribbean

wide Democratic Labour Party. It is only

after the stunning election defeat of July 1959 that the JLP withdrew its

bipartisan support and Norman Manley displayed his remarkable democratic

credentials and full respect for ‘people power’. Once the Referendum had taken place, the verdict was accepted. “We will face one

future and we walk on one road together.”

Whatever claims maybe made from political rivals or mean

spirited people, no one should decline to confer on Norman Washington Manley

his due as the Architect in Chief of Independent Jamaica.

Uncertainty

had ended. Manley had paved the way for

us to “be united as one people with one destiny.”

REVERSING THE CHANGE

The

birth of the PNP YO took place at a time of social and economic discontent

among the vast majority of the population.

Despite the rapid economic growth which followed the 1950s, the Jamaica of the 1960s witnessed

a period of maldistribution of wealth and income.

We

witnessed the migration of the rural poor to the city, an ever growing social

malaise, the breakdown in social life, and increasing anti-social

behaviour. The Corral Gardens outrage,

the Chinese Riots and the Walter Rodney demonstrations, all pointed to the

resurgence of a deeply entrenched social and cultural way of life, reminiscent

of a colonial past.

Unemployment

doubled to 24 percent during that period, and was higher among the age cohort

15-24 in the face of a demographically growing youth population.

There was also a popular radicalism which emerged during that

period, a heightened black consciousness which was either expressed through a

militant and sometimes dogmatic approach to political action, or the

African-based spiritual ideology of the Rastafarian movement and the promotion

of a way of life that rejected the symbolism and culture of the existing

‘Babylon system’.

The process of change in the 1960s seemed to be in reverse gear

and certainly antithetical to the true meaning of self-government.

So that by 1969, the leadership of the Youth Organisation would

naturally be symptomatic and

representative of the disparate streams of contending political forces and

ideological tendencies that were both a reflection of the variegated and

contradictory nature of our economic and social underdevelopment, and the

restless urge for radical change in post-Independence Jamaica.

SOCIAL

TRANSFORMATION

As the main progressive forces coalesced around a common

goal, the PNP began to reflect a melting pot of ideological tendencies under

its banner. As to be expected, the Youth were at the forefront in the march

of progressive politics. There were

those in the PNP YO who saw their role as specific to the youth of Jamaica and

as such their interests would at all times predominate over any other Others saw their role as the arbiter of the

Party’s adherence to its democratic socialist principles and defending the interest of the youth in that context.

When the PNP came to power in 1972, Michael Manley immediately

set about the task of putting into place policies and programmes to advance the

interest of the majority of the people. It advocated a more activist role in

international and regional affairs by promoting closer cooperation with the

Third World through foreign policy initiatives and support for multilateral

bodies like the Group of 77, the UN, the

Non-Aligned Movement and the ACP Group.

It was a period in which the PNP understood that the responsibility of

leadership could not and should not ignore the pernicious influences of

contending global forces. Nor should its assessment of post-Colonial society

ignore the socio-cultural dynamics of the various classes in Jamaica. The Party’s Manifesto provided the roadmap. The PNP’s performance in the first three

years in Office was a tour de force

and successfully embarked on a path of social reconstruction.

Last Sunday, we

observed Bastille Day – which for many historians spawned a new era of

democracy. During the 70s, the poetry

of Wordsworth at the time of the French Revolution, said it all –

“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive

But to be young was

very heaven.”

Much of the YO’s criticism of the Party in government was

about pace and some was directed to ensure that the Party honored its

commitment to addressing the economic and social structures of the society in

order to bring about equality and social justice.

Our Party’s structure was established to facilitate

contending ideas within the parameters of its philosophy. Democracy is rooted in its objectives, for it

was only through the free and frank exchange of views and the facilitation of

open dialogue that the Party could thrive.

Whatever radical ideas emanated from the Youth Organisation

must first of all find free expression in the forums of the Party, and secondly

must be subject in the final analysis to the true test of our democratic

tradition. I can proudly say as a

Party that we continue to score high on both counts. The intensity of the debates of the 1970s and

1980s, the positions and counter-positions which occupied hours and hours of

discussions, reflected the intellectual ferment within the Party as a healthy

expression of our democratic process and living testament to the creed of

people power.

It is in that context we must judge the role of the PNP Youth

Organisation over the years. Its

positions and decisions, however radical and idealistic, have always been afforded

full and free expression within the structures of

the Party.

That must always allow the discharge of its unique role to advocate a

position that reflects the views and advances the interests of that important

section of the population which is its solemn duty to represent.

The leadership of the Party may differ with them, at times even

vehemently so. But however much the

Party’s leadership may perceive the position of its youth arm as unacceptable

or impractical, the avenues of free

expression must on no account be stifled to prevent a vigorous exchange of

ideas. If we are supremely clear as to

our position, confident as to our approach and committed to the cause, then we

cannot shy away from the battle of ideas and the persuasiveness of contending

arguments.

APPRENTICESHIP

No matter the age, there is always a price to be paid for

political opportunism. Only grave

diggers start at the top.

Many young and ambitious adolescents who wish to climb hurriedly

to the top of the ladder, in a Party

bereft of ideological content and without the benefit of sober apprenticeship,

soon discover that once they challenge the internal status quo, their path is

blocked and they are thrown under the bus.

The PNP is proud of its record to stimulate the flow of ideas

and to welcome pulsating contests for political office.

Yesterday’s revolutionaries often become tomorrow’s models of

orthodoxy. Several of those who were once

rejected by the Politburo for ideological impurity have eventually found their

niche as captains of business while others

suffer little discomfort sitting in their bureaucratic chairs.

THE

VANGUARD

Every arm of the Party or affiliate of the Party, must

accept the supremacy of the Party’s

constitution. Its principles and objectives

must override all else if the unity and purpose of the Party are to be

maintained within a plural and democratic structure.

If at times, there appears the semblance of chasm, the source

and cause can usually be traced to breaches of discipline or departures from

established procedures. When there is

a breach of Party discipline, the constitutional provisions for hearing and

sanction must be applied.

Over the years, the Party’s

leadership has accepted the

sincerity of the YO position. The Youth

Organisation has every right to resist any attempt to compromise on the Party’s

principles and objectives, or to complain when it seems too slow in advancing

the agenda for social and economic change.

There has been and will always be complex

issues, highly contentious, where

differences of view inevitably appear.

They have been and will always be issues which test to the very limit,

the Party’s capacity to maintain its enduring principles and to define its

objectives within the context of national

aspirations and exogenous factors. A

dynamic youth arm can only enrich the debate, strengthen our resolve and help

in advancing the greater cause of this noble Party.

The YO, during its life-span, has never shunned the debate which is essential to a Party anchored

in principles rather than the eccentricities of leadership. It has pushed for programmes of political

education. It has represented the interests of the Jamaican

youth within the broad framework of building political consciousness and articulating

the Party’s philosophy in clearly defined language among the youth

population. Over the years, successive

members of its leadership have advanced the cause of youth within the Party and

the Government.

Invariably, youthful

impetuosity has always to be tempered by experience, which is neither a

reflection of ideological impurity nor a descriptive reference to ideological

weakness or vacillation. The truth is

the idealism and exuberant nature of

youth are essential to create a proper balance with experience and pragmatism

in a dynamic Party.

NEW

PARADIGMS

The

PNP has endured for 75 years because it has a clear mission which it has never

abandoned, but has remained conscious at

all times of the contemporary realities which can never be ignored.

The

prevailing orthodoxy of a unipolar world was mainstream thinking in the 1990s. There was the need to structurally adjust

our economy to meet the imperatives of globalisation.

New

paradigms had to be constructed and conveyed in contemporary rhetoric. History will record that the Party rose to

that task. The policies pursued by

Michael Manley and the PNP, on the Party’s return to power in 1989, and

subsequently under my leadership were always guided by the compass of equality

and social justice. We remained focused on the development of a

quality society and reaped the huge advantage of being a Party committed to the

People and our Nation.

THE DANGER

OF APATHY

Right across the globe, questions are being posed with

respect to structures of government, systems of good governance and the levels

of individual involvement in political organizations.

People want a stronger voice – a greater say – on matters

which affect their daily lives and yet are hesitant to become engaged in the

political arena.

The world has grown increasingly restless. Interactive structures and institutions

which have taken centuries to take root in shaping social identity are now

exposed to losing their place to new forms of association – some of which exist

almost entirely in virtual space.

Any

political Party, which fails to ride the sweeping tide triggered by the

tremendous spread of information technology in the digital age does so at its

mortal peril. The strategic use of

social media, moving us beyond

traditional methods of political organization, can be a powerful tool in

averting political apathy.

There

is mounting evidence globally that social networking sites are already

transforming democracy, by allowing the man-in-the-street, and their political

representatives to communicate and interact in ways never before thought

possible.

The

flows of online communication exploding into civil and political unrest and

movements as we have seen in various parts of the world – Brazil, the US, the UK,

Egypt – demonstrate the significant role of the Internet and online social

media in national and global political change.

Undoubtedly,

to remain effective these have to be used strategically as part of the arsenal

of communication tools so that there is no room for apathy.

Today,

each person has the ability to be an active participant in the political

process, to directly impact the process. Virtually everyone here now has at least one

cell phone which in today’s smart media era has more reach and power than the

mainframe computers of yesteryear and also challenges the reach and

effectiveness of traditional mass media channels.

Users

accessing social media networks range from toddlers to adults and the elderly,

every one of whom has an opinion and is no longer content to accept the

message. Those sending messages are now judged by the promptness and relevance

of their responses to questions. Our youths today are demanding to be seen,

heard and inspired politically. This is

not a time for apathy.

Social

media channels are now proving to be the best way to connect with our

communities because of its viral nature, ease of use and low cost. The

challenge, however, is how to utilise the best strategies that would achieve

the desired outcome.

However,

while we charge ahead with social media

and all the bright opportunities

offered, we must not abandon the

true and tried grass roots networking

strategies which allow us to physically introduce ourselves and our

programmes to those in our communities.

For

the YO to remain relevant as an important political and social vehicle it also needs to draw on its collective

genius to achieve the kinds of change you see as essential in moving forward.

You must keep ahead of the curve and make today’s youth, who are heavily engaged in social media, return to

full engagement in the political process.

PURSUING

THE MISSION

Of course, there is a major difference between perception and

reality – on both sides of the political divide – but the outcome of young

talented citizens opting away from the

Political process through voting and membership is a worrying development.

The challenge that the Party must overcome and which the

Youth Organization, the patriots, the Women’s Movement, the Outreach and

Recruitment Commission, the Policy Commission face – the entire movement

included is how do we – having recognized this challenge – retain our position

of prominence and of relevance among our nation’s youth.

This “mission” has to be among the motivators within our

minds and strategies as we commemorate our 75th Anniversary. As much as we conclude that our way of

being, our Constitution, our Culture within the Party and how we organize have

served us positively over the 75 years – we must also accept and understand

that we also need to embrace a permanent commitment to transform and to achieve

relevance and utility for our youth.

For me, and at the vantage point from where I participated,

it is no longer either or, it has to be both.

We are correct to celebrate and commemorate our history and our

achievement. But that commemoration

must not only be born out of nostalgia.

It must be guided by a desire to continue to deliver on

behalf of the people of Jamaica, credible developmental options and programmes

that will achieve the value propositions set out in the Vision 2030 document.

Our commemoration must be undergirded by the Progressive

Agenda which restate in the modern context our commitment to Participation,

Accountability and Responsibility.

Our commemoration must be aligned with the abiding philosophy

of the Founders and Pioneers that the People’s National Party will

“unswervingly aim at all those measures which will serve the masses of the

country.”

While it is true that we have continuously delivered on this

tenet of who we are – it is equally true that the needs of the masses of the

people to become equally expressed within contemporary have also changed.

The issues of access and of representation have largely been

resolved. But no one can deny that the

issues of equality and of justice are at best “works in progress”.

Moreover – the definitions and understandings of what

justice, equality and access mean are also changing to reflect the plurality of

today’s society and more so of today’s youth.

Such dynamism is a feature of human societies. However, the pace of the change has never been greater

than it is today and by tomorrow, with the next generation of innovation, that

pace will quicken significantly.

What therefore are political organizations to do and what therefore

is the role of young people within a political party? Political Organizations by their very nature

are in the business of leading social, economic and therefore human

development. There cannot be an alien

process to determine the Agenda items for the populace as to their

understanding or opinions of what social and economic development is.

In other words – the process to articulate a vision and a

response (a manifesto or other tome) that would resonate with the populace must

begin with, include and end with the active participation of the populace. To remain ahead of the wave, youth are of necessity a key component of the

process. If we are to achieve

credibility of message, of vision and of execution of policy there has to be an

in-built information capture system which is not limited to virtual or

vicarious relationships but must again achieve popular membership across all

strands and segments of the Jamaican Society.

I could put it another way.

Before we can walk the walk, we need to be able to talk the talk. But to talk the talk, we need to understand

the language of the youth and of the people.

We need to understand their motivations, their challenges and their own

idea of self actualization. But it is

not a one way street approach. We must also infuse their motives and ideas

with our principles and our own vision and understanding of the Quality Society

we seek to achieve on their and our behalf as set out in Vision 2030.

DECLARATION

75

It is this conclusion that provided the Genesis of

Declaration 75 and the Transformation Process – both of which must be treated

as living legacy elements of the 75th Anniversary Commemoration.

We intend Declaration 75 to be a tangible outcome of the Transformation Process

that seeks to document where we are as a Party with respect to where the

critical mass of the population requires us to be. Ultimately, political organizations exist to

work in the service of the citizenry – we therefore need always to understand

the products and services that society requires of us. As long as we can continue to advocate for

the attainment of those agreed products and services, and lead the articulation

of those needs – while successfully advocating for the attainment of those

ideals – we would have retained relevance well into the future.

That “mission” will however evade us if we continue to allow

our membership to shrink and for increasing numbers of our citizens to see us

as inimical to their way of life or an impediment in their own drive to fulfill

their dreams.

If it hasn’t yet become clear – let me make it explicit – the

role of young people in politics, - the

role of the Youth Organization within the People’s National Party is

inextricably linked to the survival and continued success of our National

Movement. The relationship has to be symbiotic.

Similarly, the Youth Organization as it reaches its own

maturity must begin to appreciate that it too faces challenges of relevance, of

attractiveness and of credibility. It

must also be introspective and begin to outline new ways of organizing itself

and communicating on behalf of Jamaica’s youth. Thousands of Jamaica’s youth, here and

abroad, are filled to the brim with ideas, innovation and proposals for our

country’s development and are not opting

to contribute those through the YO or

the Party.

We must grapple with the reality that an expansive and

boundless constituency of young people with promise and potential are remaining

on the periphery of politics to the detriment of our movement and our country’s

capacity to achieve the quantum leap that is required to close the equity gap.

CONCLUSION

I have attempted in this first public lecture to address the

central question – “Conscience or Chasm” – within a historical and contextual

framework, hopefully without indulging unduly in “lexical semantics”. I have spent considerable time in tracing

the Party’s roots, which so wide and deep, and its ideological origins because

I do not believe any of its branches can be entitled to the right to be the

conscience of such a democratic Movement.

Neither do I think the YO would still be alive at 45 if there

had been such a gulf or breaches of such severity that it would not have been

dismembered long ago. It has been more

of a catalyst than a chasm.

I have therefore concluded, instead, that the YO has been and

must continue to be the vanguard, to ensure that the torch which was let 75

years ago is never extinguished, that the synergies which exist must be

nurtured and nourished.

In politics, as in life, everything has a cost. The Party with a clear ideological framework

must be prepared to pay the price for dialetics – if only because its absence

comes at an even higher cost. For

without any binding agent – a political creed – the personal conflicts and

bitter squabbles are bound to be frequent and likely to recur through outbreaks

of internecine warfare.

As we mark this milestone of pour 75th Party

Anniversary, and the 45th of the YO, let us draw strength from the

rich legacy of our forebears, the noble traditions which have been entrenched

and the mission of full emancipation on which we have embarked and move beyond

today and march onward tomorrow.

What better way can there be to end than by adopting the

words which our Founder uttered at the Ward Theatre on that historic Sunday,

September 18, 1938 –

“If we start aright, if we never desert our own principles, if we

believe in what we are aiming at, if we appreciate those who regard this

country as their home, those who believe that a real civilization is possible

for people of mixed origins, if we never allow people to deflect us from our

goals, those who would like to continue to live in the feeling that Jamaica is

the grandest little country to make their living in, and the nicest country in

the world to visit – if we can do those

things and be true to what we believe in, true to the ideals we have started,

and if we can combine that with hard work and practical intelligence, and with

a readiness to do that work and show that intelligence in our own affairs, then

I believe we will have created a movement which is like nothing else started in

Jamaica, and make of this country a real place that our children will be proud

to say “We come from Jamaica.”

No comments:

Post a Comment